Chaos and vitality in Surinamese rainforest

German-born Ursula Neubauer has lived and worked as a visual artist in Amsterdam since 1983. Her work can be seen in museums in Barcelona, Okinawa and Pittsburg, among others. In 2022, she stayed at ArtCeB (ArtCenter Botopasi) in Suriname.

In early October 2022, we are on the Suriname River in a large wooden boat. In the front, under a large black plastic tarp, bags of fruit, rice, vegetables, a refrigerator, chairs, backpacks, giant bags and our two suitcases. On board the helmsman, some native villagers with children, two tourists and us, on our way to Botopasi, a Saramaccan village of two hundred souls.

... our cabin, consisting of a small bedroom with a modest bathroom and a patio covered with corrugated iron sheets

The Saramaccans are descendants of slaves from West Africa who fled the plantations in the seventeenth century, learning from the natives to survive in the forests and preserve their culture. The afternoon sun is bright, but there is a pleasant breeze on the water, thanks to the impressive speed at which the helmsman manages to race upstream. Three and a half hours later, we disembark on some rocks and climb up a steep staircase. Walking further up, our host Harry Wens guides us to our cabin, consisting of a small bedroom with a modest bathroom and a patio covered with corrugated iron, which for the next few weeks will serve as our studio, study, living and dining room, meeting place and observation platform.

My partner, physicist and essayist Frans W. Saris and I are here at the invitation of Isidoor Wens, son of this village and now visual artist in Den Bosch. He founded ArtCeB (art center Botopasi) in 2011 and has since offered a number of foreign creatives the chance to live and work in the middle of the village community with a minimum of Western comforts. His idea is to let the villagers, through the presence of creative working visitors, come into contact with a very different culture and to let the guests in Botopasi, outside their comfort zone, experience a world where the residents are closely connected to nature. Harry, Isidoor's brother, accompanies us wherever we go and is open to our questions regarding customs, rituals, and way of life. Trained as a technician and electrician, he is able to mount solar panels on our roof, allowing us to use electricity outside those few hours allowed by the government.

... to introduce villagers to a very different culture through the presence of creative working visitors

When we applied for this residency, we had deliberately left open what exactly we were going to do, because the bush of Suriname was terra incognita for both of us. What Frans did have in mind was to investigate how the population on the edge of the jungle interacts with nature and to what extent the modern world with internet and cell phones has already changed people. Together we planned to make an art book with texts by him and images by me*.

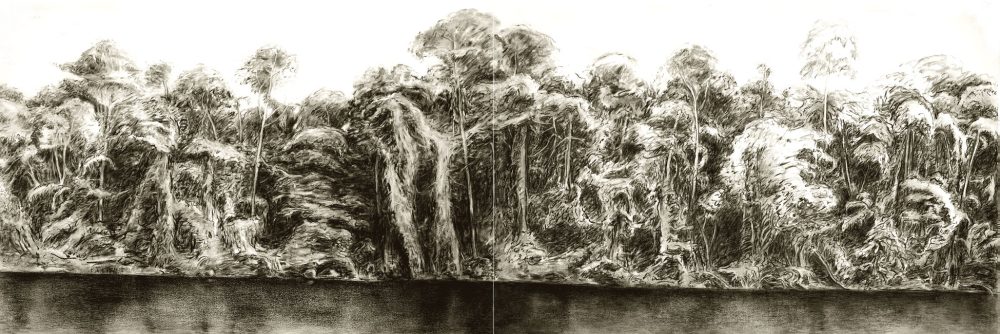

In the Netherlands, I make large prints and charcoal drawings, which I often integrate with videos. Because I didn't want to depend on the computer - the Internet functions unpredictably in the village and only by phone - I took only drawing materials, watercolors and paper, and of course my camera. Making art here is a very sensual experience, you are part of an unpredictable and chaotic nature. She forces you to enter other rooms of your mind.

There is no separation between art and life or thoughts and observations. Observation, memory and knowing interact and enrich each other. Standing outside nature is not possible. The sun and heat are unrelenting. Thunderstorms strike suddenly without warning, thunders roll over you, rain clatters deafeningly on the sinking roof, deluge-like rivers and pools flow past the house and stop suddenly. In no time the water is swallowed up by the thirsty ground.

Observation, memory and knowing interact and enrich each other

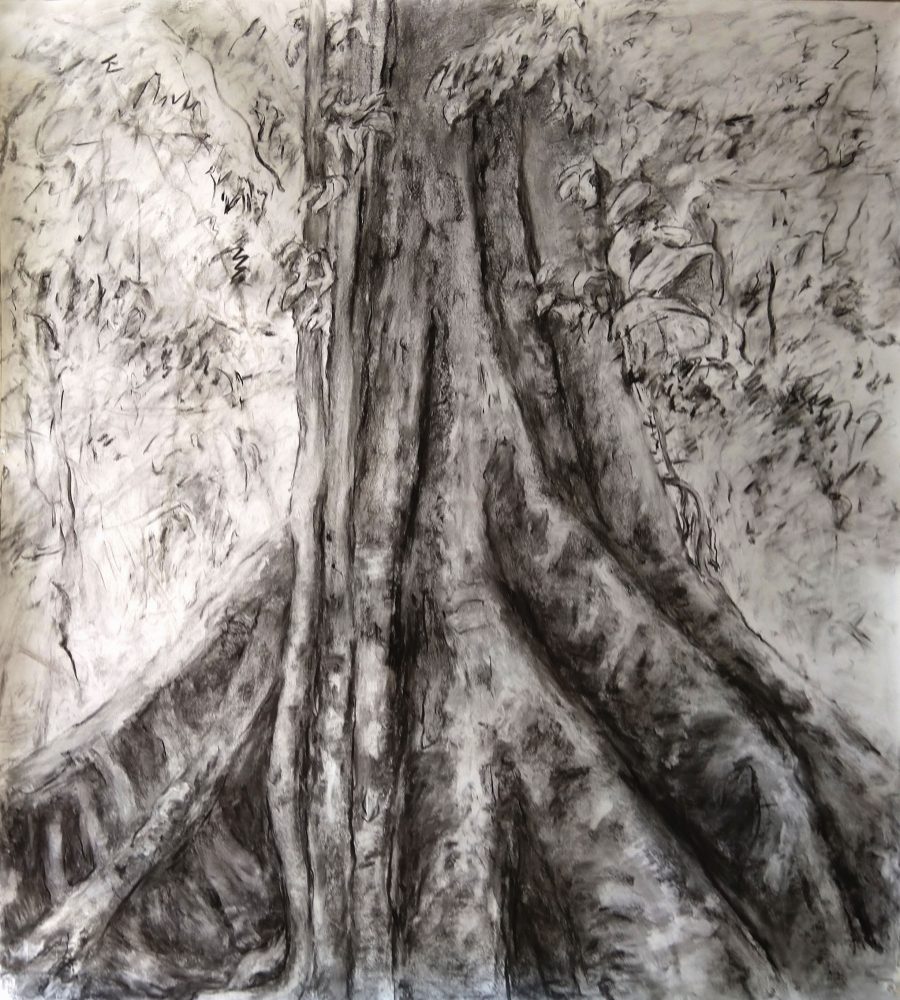

Mosquitoes and ants are everywhere and seem to particularly like my watercolors. My legs show ever-changing patterns of bites and veins swelling due to the heat, resembling the tree roots of the large mango trees in front of our hut. The hygroscopic drawing paper bulges and undulates in all directions. At night after seven, when the fluorescent lights on the patio come on, the ground in front of our hut teems with toads and insects. On the first night we had a visit from a rat and a bat. A huge black butterfly flies in the bathroom; lizards are ubiquitous. The sounds are delightful, a squeaking and chirping of tropical birds, the swelling sound of cicadas and then suddenly silence. From 6:30 in the morning we hear the women of the extended Wens and Petrusie family, our hosts and caretakers, raking and sweeping the ground, shouting messages to each other, rattling zinc tubs. Never in a hurry, everything goes as it goes.

We start the day with a cup of tea, in the process greeting our neighbors and the children who are washed, in green school uniforms and umbrella against rain and sun, going the short way to school established by the Zeist-based Evangelical Brethren Church (EBG). After breakfast we work for three hours, then swim in the river, lunch and siesta and another three hours of work. The children especially are curious, they come to us of their own accord as soon as they see me drawing, they want to and they will keep coming.

After breakfast we work for three hours, then swim in the river, lunch and siesta and another three hours of work

Subjects abound. One cannot help but draw on the ingenuity of nature, its forms and structures that one could not conceive of on one's own. Drawing, I learn to understand the seventy-meter tall kankantri with its majestic root system and large umbrella. It is considered sacred by the natives and spared when cutting down the forest for a living or mining wood for boats, cottages and furniture. Canoeing along the river, you recognize it among lower forest stands as a lone sentinel of the jungle.

The oil-bearing orange fruits of the maripa palm are bundled in a cluster of nuts, each with a wooden cap stretched over it. The unfertilized clusters hang from the tree like limp tassels. Some palms have very pointed, poisonous thorns at the base of their leaves to protect themselves from animals.

There is no animal husbandry and almost no pets, because that demands too much food and there is none

Nowhere is biodiversity more evident than here, everything is intertwined with everything else. Everything grows and lives in symbiosis with each other, including the villagers. For they still live as they did three hundred years ago in small, very basic huts, men and women each in their own hut. The children live with their mothers, aunts or grandmothers. The boys from puberty on with the father to learn male skills. Men are still allowed to have three wives side by side, but are expected to be responsible for the families. Women are allowed to divorce husbands if they are no good. There is no animal husbandry and there are almost no pets because that demands too much feed and there is none.

The Saramaccans live off the crops they grow themselves on boarding grounds. In the dry season when there are no fresh fruits and few vegetables to harvest, they get them by boat from Paramaribo and the surrounding area. They fish in the river and supplement their diet with occasional self-shot game. But the beasts realize this too and hide in the jungle, which is why you hardly ever see them.

Many small villages we visited in the area appeared to be depopulated

All villagers have drinking water and a cesspool. There is medical care nearby, a church and access to the world via cell phone, made possible by a high mast a few hundred meters from their homes. Primary education is compulsory and secondary education is almost the norm in Botopasi. Children are sent to Paramaribo for further education and training, usually living with a family member. But this progress also has its negative effects, as most young people do not return to the village. Many small villages we visited in the area were found to be depopulated.

Yet, as visitors, we have retained the hope that this oasis of symbiotic life with nature will be nurtured by some higher-educated natives, so that they return from an urban life to the simplicity of this existence in nature and, as teachers, nurses, medics and technicians, make their contributions to the survival and progress of their village and offer hospitality to artists in ArtCEB.

Still, as visitors, we have kept hope that this oasis (...) will be nurtured

As a farewell to our stay, we invite our neighbors and their children to a presentation of our "harvest": drawings, photos and videos in which they can recognize themselves and their surroundings. The presentation must be done through a TV screen so that people can see the images even from a distance, not an easy task, as the technical resources are limited. Frans reads three short stories about our life in the jungle. The next morning we leave Botopasi by boat, rich in experiences and with lots of material for further elaboration.