Zetland*

Wilma Vissers works and lives in Groningen. She graduated in painting and printmaking from ABK Minerva in 1989. Her artworks have been shown in international group exhibitions in Moscow, New York and London, among other places. She was artist-in-residence at the Heinrich Böll Cottage and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre, both in Ireland. This is a story about a stay at the Booth in the Shetlands.

In recent years, I have stayed at various artists' houses or artist residencies to work there for a period of time. I prefer to go to an island where the weather is bad. I want to be close to the sea and see barren landscapes blown clean by sea breezes. Staying in such places follows a familiar pattern for me. First week: getting used to a place and not yet realizing where I am. Second week: everything comes in and I want to gather as much information as possible about the country and landscape where I am. Third week: I usually succeed in meeting fellow artists. Fourth week: I can carry out the ideas I had beforehand about my stay.

Why am I doing this? I break free from my daily "comfort zone" and try to think freely, allow strange influences and make unexpected choices. To have contact with nature, open spaces. Away from the stuffy Dutch I know far too well. Meeting fellow artists abroad to get acquainted and to hear how they experience being an artist. Gaining knowledge and experience about something I don't know yet.

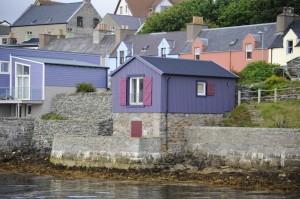

This time I stayed for a month in the Booth On the Shetland Islands. A northern archipelago that is a part of Scotland. The Booth is a small building, quite suitable to stay for one person and is more or less in the water in the harbor of Scalloway, the former capital of Shetland. With a little wind, I can feel every wave washing against the little building. I constantly felt like I was staying on a boat during this month. It is very light because it is the month of May and it is still only 3 hours of darkness per day. The night sky remains light and I sleep poorly.

This time I stayed for a month in the Booth On the Shetland Islands. A northern archipelago that is a part of Scotland. The Booth is a small building, quite suitable to stay for one person and is more or less in the water in the harbor of Scalloway, the former capital of Shetland. With a little wind, I can feel every wave washing against the little building. I constantly felt like I was staying on a boat during this month. It is very light because it is the month of May and it is still only 3 hours of darkness per day. The night sky remains light and I sleep poorly.

Before coming here I had a different expectation of this island group. I thought it would be more Scottish. However, it has a great Scandinavian influence. This is reflected in the architecture which also shows traces of Hanseatic influence. It is on the border of several historical spheres of influence. Until the end of the Middle Ages, the archipelago was Norse and people spoke Norn. A mixed language of Norwegian and Icelandic. The Njuggle, for example, is known here. This is a fabulous animal in the form of a pony that carries the rider far out to sea, only to dissolve into nothingness, with fatal consequences. Often, however, it ended with a wet suit and the Njuggle disappeared into the sea like a blue flame.

Before coming here I had a different expectation of this island group. I thought it would be more Scottish. However, it has a great Scandinavian influence. This is reflected in the architecture which also shows traces of Hanseatic influence. It is on the border of several historical spheres of influence. Until the end of the Middle Ages, the archipelago was Norse and people spoke Norn. A mixed language of Norwegian and Icelandic. The Njuggle, for example, is known here. This is a fabulous animal in the form of a pony that carries the rider far out to sea, only to dissolve into nothingness, with fatal consequences. Often, however, it ended with a wet suit and the Njuggle disappeared into the sea like a blue flame.

The Shetland ponies I see here do not exhibit that tendency. During long walks I take here, they approach me very curiously and expectantly. Just like the seagulls, terns and skuas that circle dangerously close over my head as I walk through their breeding grounds. There are birds everywhere. The sound is very present as are their flight movements in the air. The landscape is bare and open and with traces of former inhabitants.

Roads didn't used to exist. Therefore, many abandoned Crofters cottages are located in very deserted places close to the water. These ruins are made of rough blocks of stone stacked on top of each other. The holes that served as windows could never have contained glass.

During a tour of the Shetland Museum, I saw the Shetland Knives. These are pieces of stone that were used as knives in prehistoric times. They had a perfect flat shape and were made of granite with a beautiful texture. A very exciting abstract form that could so play a role in fundamental painting. How could that be my experience? I experienced the same surprise and pleasure as when seeing a very good work of art.

I met with an American artist, Roxane Permar, who has lived here for many years and teaches in Contemporary Textiles at Shetland College. This is the University of the Highlands and Islands, with a department of art and culture. Roxane makes visual work in which knitting and textiles play an important role. I have seen a knitted cover for a tank and a knitted house of hers in the Shetland Museum. She was doing this even before the phenomenon of wild knitting was so popular. She calls this, therefore, somewhat mockingly yarn bumming.

I was invited to a private view of the final presentation of the third year textile students at Shetland College. The three students - very appropriately - presented textile works in the form of woven cloths, post-modern wool garments and a very fragile cardigan made from bamboo thread and silk. Very beautiful all of them. This was displayed in the rooms of the Textile Museum which is located behind a large ugly power station building in Lerwick, the capital of Shetland. I found it amazing that a year of study can consist of three students. In the Netherlands, such a thing would not be possible. The department would be disbanded or merged with another department. Apparently market forces have not yet penetrated here; a relief. When we left afterwards and the building was locked, the key was placed under a stone.

After this I spent a few days on Unst, the northernmost island, the size of Texel, where only 700 people live. The landscape on the spot reminded me very much of the Irish landscape. I met with Tony Humbleyard, an English sculptor who lives and works in a remote lighthouse keeper's house. His work consists of installations of things he finds on his daily walks along the coastline. These may be whale bones or other objects returned by the sea. Tony lives in a very remote place. He doesn't own a driver's license or a car, digs his own peat and takes a sea bath every day. I admire the quirkiness of his lifestyle. He makes intriguing work and knows very well how to use the things or proceeds of the sea and the land and give them a very individual form.

In Shetland, 1% of the proceeds from oil and gas discoveries are invested in the local economy. Every village has a swimming pool and there are visitor centers in nature reserves. The Mareel - a large cultural center in Lerwick - derives its existence from this. The Booth also came into being because of this. The aim is to bring artists from Shetland into contact with artists working internationally. Since this year another residency has been added, in a lighthouse on the southernmost tip of Shetland, on a very high piece of rock overlooking the ocean where Orcas can sometimes be seen. I always started the day with a long walk. The first 14 days of my stay the weather was beautiful and warm. You can just walk through any field here and climb over any fence or barbed wire. All of that is allowed. The ground is soft and springy and not very wet. There are almost no paths. Along the way I saw more birds, many sheep and young lambs. The mountain hares shot ahead of me as I approached. They had heard me coming from very far away. One of the walks ended on the airport runway. There was a man behind a barrier there and I was not allowed to walk through until two planes had taken off. It turned out there was a family who had once chosen this as a picnic spot. Since then, this man has been there to prevent this from happening.

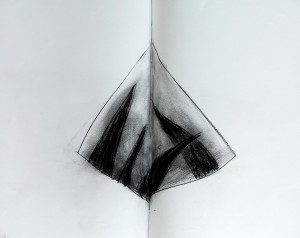

I created a series of prints in the Booth using found pieces of plastic and other objects on homemade handmade paper. The minimalist imagery I often use goes very well with the unexpected nature of the found materials. This use of a plastic form, smeared with paint and then printed on homemade paper, for me, represents very well what a stay in Shetland does to me. I would never be able to think of this at home.

This was my sixth residency. It still amazes me how the shifts in my moods seem to merge with the light on the ocean water that I have a direct view of. That's good. I am getting to know another side of myself in this month where everything is new and nothing is familiar.

*Setland is the old name of Shetland

www.wilmavissers.com

www.roxanepermar.com

www.tonyhumbleyard.com