I love Beirut

Judy van Luyk is a visual artist, graduated from the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam and specialized in site specific art at the Academy of Arts (HEAD) in Geneva. In November and December 2018, she had a six-week residency in Beirut, organized by the Beirut Art Residency (B.A.R.). For this, she wrote a proposal for an art project in public space and travelled to Beirut to research the city and further shape the project.

He spoke of a city of contradictions. A city where neglected buildings stand next to modern, shiny skyscrapers.

Before I travelled to Beirut, I talked to a friend who lived there for six years. I knew that Beirut is also called 'the Paris of the East'. But his stories about a complex city with endless traffic jams, corruption and pollution were new to me.

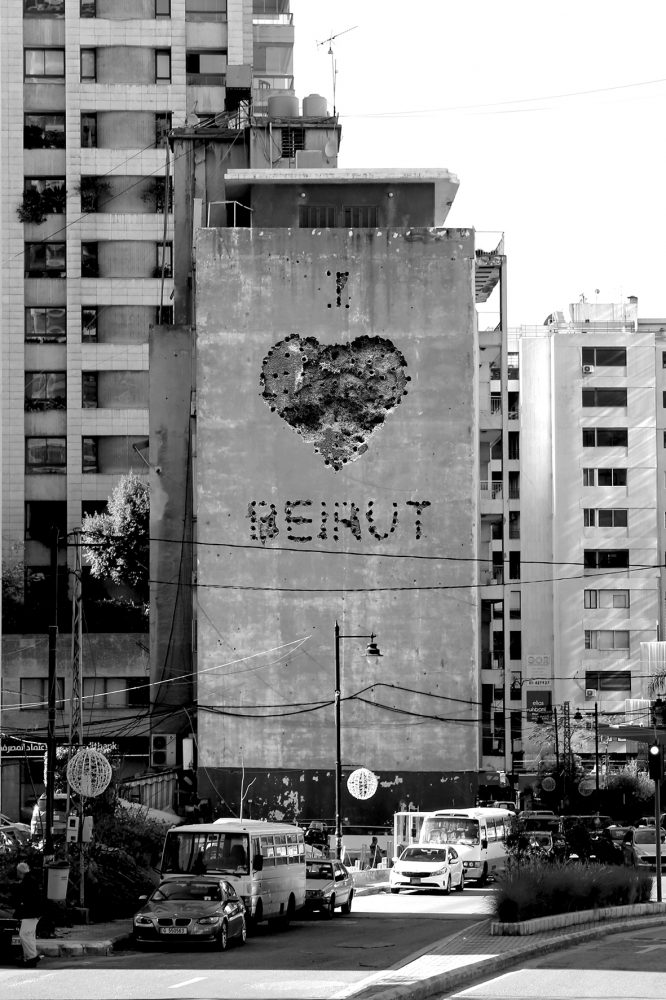

He spoke of a city of contradictions. A city where neglected buildings stand next to modern, shiny skyscrapers. A place where the bullet holes, like scars of war, are visible and the balance of peace seems shaky. But at the same time, he spoke passionately about the friendliness and zest for life that typifies the people of Beirut. They love their city and hate it at the same time. And once you've been there, he said, you want to go back again. At that moment I could not quite grasp this, but I hoped to love this city just as he did.

I wanted my project in Beirut to take place in public space. In the Netherlands, I've been drilling holes and recording the process of decay. I drill as many holes until the wall falls apart. I make recordings of this and edit them into a stop motion video, expressing the process of decay. If I were to do a similar project in Beirut, what would it mean in a city where there are already so many holes and decay plays a big role? I put it to the team of the Beirut Art Residency. They agree with me that a project involving the drilling of holes could be very interesting here, but that it is difficult. You can't just do anything with holes, because the war is still so fresh in the memory. They also say that the people are not waiting for an artist from the West to come and kick up a sore point. They would prefer not to be reminded of the war, even though it is still visible everywhere. Politically, there's also a lot going on, so my work could be interpreted very differently on one building than on another.

If I were to do a similar project in Beirut, what would it mean in a city where there are already so many holes and decay plays a major role?

So I started researching the various buildings, their owners and their political backgrounds. At the same time, I looked for the form of my 'hole-drilling project', I looked for a positive way of saying that decay is okay and that a monument to war is allowed.

During that search I soon found out that public space in Beirut is scarce. There are few parks and squares. Only 0.75% of the city's surface seems to be a public space. In an average European city this is about 12%. There is one public beach, but it is littered with plastic and stinks to high heaven. That's where the sewage flows into the sea. What does 'public' mean here anyway? And how can I do something in the public space here?

I spoke with Nour Osseiran. She works for TAP (Temporary Art Platform). This organization is involved with art in public space. TAP recently published a manual. This is a pdf of 75 pages entitled A Few Things You Need to Know When Creating an Art Project in a Public Space in Lebanon. Very handy if you want to know what rules apply and which permits you need to apply for. Nour told me that the costs of fines are often already included in the budget of an art project. They do this because there are often many different parties involved and it is difficult to get permission from each of them.

I spoke with Nour Osseiran. She works for TAP (Temporary Art Platform). This organization is involved with art in public space. TAP recently published a manual. This is a pdf of 75 pages entitled A Few Things You Need to Know When Creating an Art Project in a Public Space in Lebanon. Very handy if you want to know what rules apply and which permits you need to apply for. Nour told me that the costs of fines are often already included in the budget of an art project. They do this because there are often many different parties involved and it is difficult to get permission from each of them.

In my work I am often busy with showing the beauty of imperfections. In a country like the Netherlands it is necessary that there are imperfections and that not everything is perfectly tidy. In a city like Beirut it's different.

The Beirut Art Residency team arranged a meeting with local artist Jad El Kourhy whose work really appeals to me. We visited his studio. It clicked right away. I find it admirable how he gets things done. For example, Jad realised a large-scale installation in the very famous, empty El Murr Tower building, which is still an army base. For three weeks, colourful curtains hung in every window, blowing in the wind. Thanks to his connections with the army he managed to get it done, but the owner Solidere had to take it down anyway. It gradually became clear to me: you have to know someone in Lebanon, otherwise you won't get anywhere.

In my work I am often busy with showing the beauty of imperfections. In a country like the Netherlands it is necessary that there are imperfections and that not everything is perfectly tidy. In a city like Beirut it's different. Different rules apply. Chaos prevails. Silence and order is a luxury here.

Every day I walked through this crowded busy city with cars and honking everywhere. To find some peace in this hectic city, I visited empty, abandoned buildings. On top of the roof of such an empty building looking out over the city, I could finally organize my thoughts.

Every day I walked through this crowded busy city with cars and honking everywhere. To find some peace in this hectic city, I visited empty, abandoned buildings. On top of the roof of such an empty building looking out over the city, I could finally organize my thoughts.

Many of the empty buildings are left over from the civil war. This ended in the 90s. There was a battle for strategic buildings, in the center of Beirut; also called the Battle of the Hotels called. One of them is the old hotel, the Holiday Inn. Whoever owned the Holiday Inn was winning. It's an empty, concrete carcass full of loopholes bigger than a door. The building is still there because the owners cannot agree on the future of this building. I realized that this is very special. I had never seen such a colossal monument before!

It's not just the remnants of the war that are abandoned. New luxury residential towers stand empty for 10%, for example. Ordinary citizens cannot afford these apartments. They are bought by rich Saudis as an investment and as a second home, but they make sporadic use of them. Other construction projects are simply never finished. Then there is suddenly a concrete skeleton between all those luxury residential towers.

My first text I drilled was: I LOVE BEIRUT, where LOVE is heart-shaped. I think a video projection of my drill action on one of the buildings in Beirut, says exactly what many people are thinking.

I photographed many of these buildings, with the aim of using the empty wall in my proposals. Eventually I want to project a video on one or more walls. Before that happens, I first had to stop motion and that means drilling holes. My first text I drilled was: I LOVE BEIRUT, where LOVE is heart-shaped. I think a video projection of my drilling action on one of the buildings in Beirut, says exactly what many people are thinking. "I love Beirut despite its war holes, eventful history and controversial politics. And some of the old buildings should not be replaced by luxury residential towers." I also drilled the lyrics I love Transparency and I Love Solidarity, a cynical reference to Solidere, a controversial real estate company.

I wanted to drill the heart in such a way that it looks like a beating heart when I make an animation of it. In reality it didn't work. The wall I drilled into was more sand than concrete and collapsed almost immediately during the first drilling session. Perhaps this is also significant for Beirut. It was a nice image though. The people on the street became curious about what I was doing. They stopped, took pictures and had a chat with me; after all, it's not every day that a crazy Western woman is drilling in the street. The police also came to take a look, but they didn't like it very much. According to the policeman it was not safe: I had no license, and I had to stop. I persisted and tried to convince him. He suggested I talk to the chief of police in the neighbourhood. Somewhat nervous I agreed. The chief of police turned out not to have a problem with it. So I was allowed to continue without a permit.

...I didn't have a permit and I had to stop.

Eventually, I had a number of proposals ready for video projections on different facades. Together with the BAR team, we decided to apply for a permit first, at the municipality. To prevent the project from being cancelled within the hour of a police check. However, the time proved to be too short to actually carry out the projections, as applying for a permit does take some time. This means that I have to go back again! Which is no punishment, because I really want to return to this turbulent city. The project will be continued; Beirut, I love You.