Timeshells, the captured time

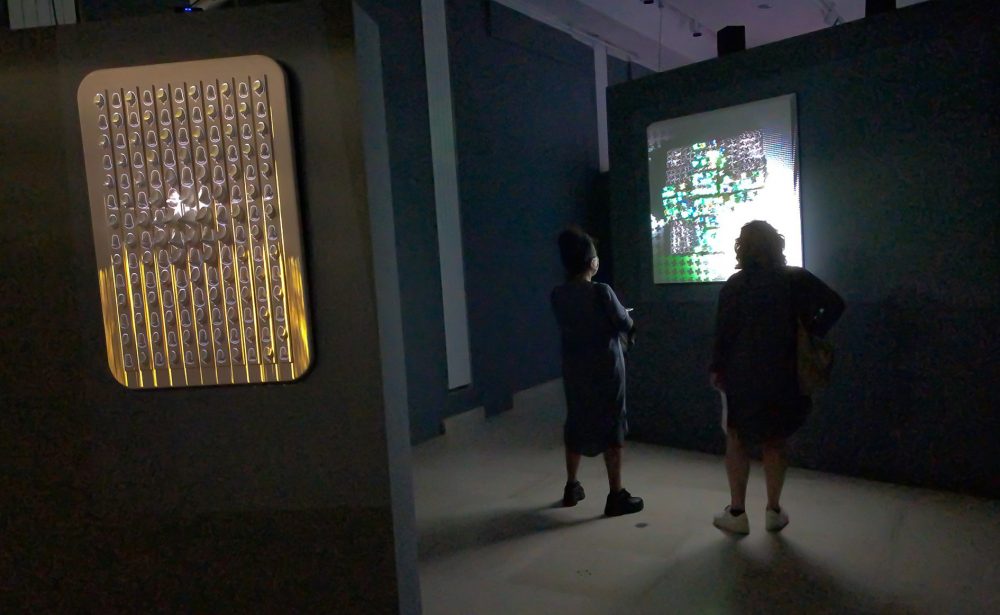

Adriaan Lokman (Haarlem 1960) makes experimental animated films in 2- and 3D, interactive and cross-media projects in which he explores the boundaries between abstraction and reality. He plays with light and shadow, camera movements and sound to create rhythm and to take the viewer into virtual worlds that excite the imagination. After the great success of his independent debut film Barcode (2002), he moves to a desolate mountain in central France and focuses entirely on independent projects. Five years ago he started the Timeshells project, installations of 3D printed objects onto which video is projected.

'I started with Timeshells Because I wanted something different. Making films, especially international co-productions, is a matter of years. Not only before you get the green light on financing but also to make it. In your mind, you're working on the same thing all the time.

I needed to express something in a faster and more direct way.

I like the phase of development the most. The experimentation to arrive at the film, developing the visual language and making sure it works is the challenge. You can compare it to a musician building his own instrument. When it's finished he still has to learn to play it. Once he can do that, part of the challenge is gone.

I needed to express something in a quicker and more direct way. I wanted to make something tangible, something you could hold and walk around. When 3D printing came along, I finally had the opportunity to make the worlds I build in my computer in real life, one-to-one. You can do that with other materials, of course, but it never works out that precisely. It's fantastic to transform what you see in your head and on a screen into something tangible. The process is also much more physical than making a film. The 3D objects have to be printed, touched up and pasted. I'm not sitting behind a computer screen all the time.

With film, you have to tell a story, you have to hold the attention, it has to have a tension curve and a beginning and an end. I find it a puzzle to get that done. The projections on the installations are loops of two minutes. I don't have to worry about losing the viewer's attention. With Timeshells I don't tell a story but I express more of a feeling or an idea. I just have to concentrate on the visual side of the concept and execution. The title refers to the common thread in the installations. By projecting from dark to light to dark, a day is simulated. Thus a day is captured in the object.

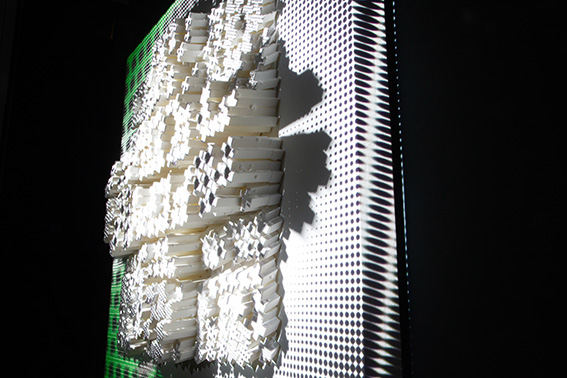

With my films the support is a flat dead screen, with the installations the support is the 3D object and that gives a whole new dimension to the projection. It is actually a film screen with a life in itself. By changing the projection, the 3D object also gets a different meaning. At Hello Welcome, the installation about spam, I had first made an animation of texts and blinking lights. Only when I had added a background with hearts did the object get the over-the-top effect I had in mind. I like to work with limitations. The technical limitation is a given but I also always choose a limitation in form. In my film Chase for example, I wanted to investigate whether I could make a believable action film with triangles. My work is always on the border of reality and abstraction. I like it when the viewer makes their own story, it doesn't always have to be understood the way I mean.

I like working with constraints

I start with a visual idea without a preconceived plan. Along the way, I do get a vague idea of where I want to go and a concept forms. I often don't really know where I wanted to go until it's finished. By now I have made ten installations. Without thinking it through beforehand, it turns out that there is a connection after all. In almost all of them my vision of today's society emerges. Pharmacity is an indictment of neoliberalism in the welfare state but also, like Hello Welcome, an indictment of all those parties who constantly demand our attention. In Pharmacity with visual lures, in Hello Welcome With spam you can hardly get rid of. If everyone yells equally loud, who can you hear?

I take pictures and record the images with my cell phone without knowing why. Like someone else collects stamps, I collect images. At some point I sit on a terrace or a train, a place where the world is moving but I don't really participate, and then an idea comes to me. For example, those pharmacy crosses. Here in France there is hardly a village that doesn't have at least one pharmacy. Always with those hysterically blinking neon crosses. It irritates and fascinates me at the same time. It irritates me, also because the pharmacy is always luxurious, with sliding doors that whizz open and expensive information systems, paid for by a pharmaceutical company. While the baker next door disappears because he can no longer make ends meet. It fascinates because they all seem similar while they are all different. Because they are all so aggressively present those differences no longer stand out. If you bundle them together they become a new thing, they sometimes look like a field of flowers with all that green and those bright colors.

As another collects stamps, I collect images

I wanted something with a city, those crosses and projection. Then I start sketching, try to put logic into it and combine. By trying things out, making little tests and by trial and error the idea takes more and more shape and I discover the story. I created a city with it, and through the excess, what is actually ugly becomes beautiful.

Of course, the objects I print also exist one-to-one in my computer. First I create the 3D model and add the light sources and camera movements. Then I have to drop the video images exactly on the crosses of the 3D model into my computer with video mapping software. The first time, that's an awful lot of work. For every exhibition I have to adjust it. If the projector is slightly higher or lower than I simulated in my computer, the image no longer falls exactly on the printed object and has to be corrected again. In that respect, I am glad that the COVID epidemic is over. Last time I had prepared everything for the Rotterdam Art Week, where I was invited to exhibit in the Sturgeon Building. Unfortunately, that was cancelled at the last minute. Fortunately, I get a second chance in May.

I live here in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of nature (...). Actually, I am constantly working in residence.

I add moving light and shadows to the to the digital version in my computer. I project this exactly as in the computer onto the printed installation. This makes it look like real light is moving across the installation which adds a strange kind of moving realism. This confuses your brain and makes the object seem to move and come to life. People often can't put into words exactly what is happening but they do notice that it triggers something in your mind. I often hear that it is hypnotic.

I live here in the middle of nowhere, in the middle of nature. People who don't know me are always surprised by that. They expect me to be inspired by this environment, but see that my work has a very strong cosmopolitan character. I get my inspiration from the city or from very different things, actually not from nature. It's wonderful to work like this, with the view of the valley in the middle of the forest. That peace and quiet helps me to concentrate. It is a necessary counterweight to all the technology I work with and surround myself with. Actually, I'm constantly working in residence.'