Føroyar

Wilma Vissers works and lives in Groningen where she graduated from the ABK Minerva in 1989 in painting and graphics. Her work has been shown at international group exhibitions from Moscow to New York. She also stayed in various artist-in-residencies, such as the Heinrich Böll Cottage in Ireland, the Booth on Shetland, the Skaftfell center in Iceland. She wrote the text below about her stay in a school now in use as a residency in Tjørnuvik in the Faroe Islands.

Very happy to be able to do a residency in the Faroe Islands after a second long corona winter and lockdown. That this is special I realize all too well. In the past I have done work periods in Iceland and on the Shetland Islands, so residency on the Faroe Islands seems very logical.

Faroe or Føroyar means sheep in Old Norse. The shape of the islands is somewhat reminiscent of a sheep. But it is also the mammal most common here, shaping the landscape by its presence.

I'm glad people live here year-round too

The residency is in a former schoolhouse in the town of Tjørnuvik (pronounced Chu-nu-vik), on the island of Streymoy (island of streams). The classroom with the world maps from school days is my studio.

Tjørnuvik is in a fairly secluded valley by the sea and there are only about forty wooden cottages, many of which have grass-covered roofs and are built in the traditional way. They look cute and doll-like. They are often second homes for people from the capital Torshaven.

I am almost immediately introduced to a goose-herding, waffle baker, nicknamed the waffleman, and the priest. I am glad that people also live here year-round. It is winter, bad weather and many residents have corona so keep a certain distance.

When I go to a residency it is often on a remote island in a northern European country. Without knowing it, in recent years I have often followed the trail of the Irish Monks. The first mention about the Faroe Islands was made by the Irish Monk Dícuil in the year 825 in the Liber de Mensura Orbis Terrae. That is even before the Vikings came here. After that, the islands were colonized by Grim Kabam from Norway.

Eight months a year it blows over 100 km per hour here

The islands are barren and rocky, about the size of the province of Utrecht. They lie between Iceland and the Shetland Islands. They are covered with grasses and small shrubs and there are very few trees. They are remnants of the Thulean plateau. A large geological landmass of lava formed during the Paleogene, parts of which can be found in Ulster (Northern Ireland), the Inner Hebrides and Iceland.

Statistically, the Faroes were once part of Norway, but now it is incorporated into a Commonwealth with Denmark and has an independent position. Eight months of the year the winds here exceed 100 km per hour and it rains much more than in the British Isles.

Because of the presence of so much weather and the influence it has on daily life, it is something that has shaped Faroese culture. The weather has such a strong presence here that there is no denying it, and conversations with residents are almost immediately about it. Public transportation, on which I depend, can regularly be completely down due to the bad weather.

Tim Ecott, an English writer and journalist I met through social media, has written a book about the Faroe Islands. It's called The Land of Maybe, kanska in Faroese. In practical terms, this means: maybe tomorrow we can do this or that, but maybe not. The winds blow over these islands with such hurricane force that often nothing is possible.

The overwhelming light falls very beautifully on the rocky cliffs and stones and can be different every five minutes

I am attracted to this kind of landscape and conditions. The overwhelming light falls very beautifully on the rocky cliffs and stones and can be different every five minutes. The beach is black and dramatic and there is still snow on the mountain tops.

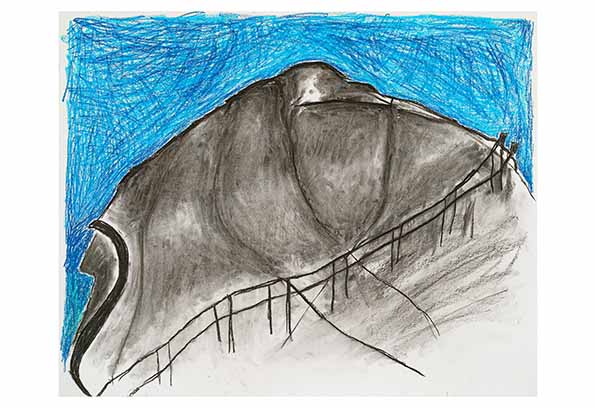

It is very crazy to realize that in a landscape with small trees, I am taller and bigger than all that vegetation. In the Netherlands I often walk in the forest under the trees and here they are at my feet. This changes the scale of a landscape and seems to invert and become intangible. I notice especially when making a drawing that it is very pleasant to include a present high voltage line in the drawing. This makes it immediately clear what the proportions are and gives me a grip on the landscape.

This is what I am often concerned with in my work as well. The effect of color, visual elements moving forward and backward, and the function that material can have. All these elements are abundantly present here. That is why I find inspiration here. As an abstract working artist, the scale of these landscapes does something to me. These images I see here I take home with me in my mind. Because of experiences like this, these kinds of residencies are important to me. I have often done residency periods in recent years. I went alternately to Ireland, Scotland and Iceland, where I worked independently but also participated in projects. I took important artistic steps during these stays.

The residency is always an inspiring experience, in which openings arise to new developments in my work

What fascinates me so much about a residency is that it is often in an environment where there is no art or where art has a completely different meaning than the one I give it or that is common in the Netherlands. This creates a separate, challenging field of tension, causing me to ask myself questions about my artistry. The residency is therefore always an inspiring experience, in which openings arise to new developments in my work.

In a place abroad where I am to work I find the naturalness again to make a drawing. This is caused by the ever-changing impressions of traveling and the chance encounters and conversations with people I don't know. Which goes well with the fleetingness of charcoal or pencil on paper. The shapes come naturally and effortlessly from my hand.

During the two years of the corona crisis, I became interested in maps. I had nowhere to go and travel could only take place in my head. Memories of previous residencies I experienced mostly in my dreams and I often looked in an old Wolters-Noordhof Atlas. This became the basis for many drawings and prints. Always this ground adds something of meaning to the forms I place over it. The shapes fly over the landscapes, so to speak. The maps are very prominent here in this building and the history that it was once a school permeates me very much. All the textbooks that were used when it was a school(s) are still there. I find many songbooks (Sangbók) here. This is in keeping with a Faroese tradition of music and singing. One example is that sailors who went sailing said goodbye to their wives, children and home by singing a song. When these men returned home safely they would sing a song to celebrate.

He asked me what do you come here to do in the winter? I said I am looking for the snow and winter

The use of maps was also the basis of my invitation to this residency. The landscape formed by the sheep and the wind is so barren by itself that it already looks like a map. The first thing I did when I entered this classroom was to pull out all the maps in front of the blackboard. Actually, the map is also a kind of drawing. But in a simplified and summarized way. Because the total of events is too big for a human head. Especially now.

The only social event that took place in this village was the church service at noon on Sunday. To talk to some people I went there once. I find that to these people I am a little bit the artist of the village after all. I had taught myself from a textbook some words Faroeese, because most of them do not speak English. This allowed me to introduce myself in their language. They all already knew I was from Holland. Halendingur (hollander) they say. I had a long conversation in English with the priest. He asked me what are you doing here in the winter? I said I am looking for the snow and winter. We were talking about the Irish Monks. The priest said we are actually all also of Irish descent here in Tjørnuvik. We now think that travel is something of modern times but in a distant past the sea was the highway of today and contacts between anyone have been as old as the world.